Image courtesy of Oxford Policy Management

From fragile to agile: how South Asia can build agile health systems for the next crisis

23 October 2025

In this article, Shaswat Acharya of Oxford Policy Management (OPM) draws on findings from several studies conducted by OPM to assess health system resilience in South Asia, with a focus on Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, complementing the findings with evidence from other sources. He looks at three domains of the ReBUILD for Resilience Framework – dedicated leadership and distributed control; availability, capacity and motivation of human resources; and availability of physical and financial resources – and presents five steps which could take the region from fragile to agile when facing public health emergencies.

[Please note, all of the following links open in a new tab.]

South Asia is highly vulnerable to public health emergencies due to a combination of geographic, socio-economic, and environmental factors, with climate change in particular leading to increased shocks. Countries in the South Asia Region, including Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, consistently rank high on the Climate Risk Index, and while comprehensive data on all climate-related deaths remains limited, available evidence reveals not only a substantial loss of life but also highlights how the climate crisis deters access to essential healthcare services (see Nepal Disaster Report, 2024). Challenges include:

- South Asia is prone to rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and extreme weather events, all of which are intensifying. The region’s geography, including the Himalayas, and its dependence on the monsoon, makes it highly susceptible to climate crisis.

- With a rapidly growing population (expected to exceed 2.2 billion by 2050) and around 600 million people living on less than $1.25 a day, even small climate shocks and outbreaks can have devastating effects, pushing large numbers into deeper poverty.

- Around 70% of the population lives in rural areas and depends on agriculture, which employs 60% of the workforce but contributes only 22% to GDP. These rural economies are highly vulnerable to climate-related disruptions.

- Melting glaciers, like the Gangotri, threaten long-term water security for 1.5 billion people living in the floodplains of Himalayan-fed rivers. This increases flood risk in the short term and water shortages in the long term, with associated risks of outbreaks.

- Cities like Colombo, Delhi, Dhaka, Islamabad, Kathmandu, Kolkata and Mumbai are expanding rapidly, with large populations living in informal settlements and lacking basic infrastructure. These areas are particularly vulnerable to climate-related hazards and natural disasters such as flooding or earthquakes, and crowded conditions increase the risks of disease outbreaks. Inadequate urban planning, poor infrastructure, and limited governance and financing capacities hinder efforts to build climate-resilient and healthy cities.

- The region also experiences frequent, often simultaneous disease outbreaks – from global pandemics such as COVID-19 to local epidemics such as Zika (see WHO bulletin, 2025) and Nipah virus (see WHO bulletin, 2025) in parts of India, Chikungunya in Sri Lanka (see WHO bulletin, 2025) and widespread dengue outbreaks affecting all countries (see WHO bulletin, 2025). Rapid urbanisation, population growth, and large-scale internal migration, often triggered by climate crisis, are altering landscapes, pushing human settlements closer to wildlife habitats and increasing the likelihood of an increase in epidemics (see The Conversation, 2020). The expansion of subsistence farming and poor veterinary oversight further intensify risks. These changes are creating conditions where pathogens can more easily emerge and spread particularly in densely populated urban centres with overburdened health systems.

Several recent climate crises, such as recurring cyclones and floods in Bangladesh (see Action Contre la Faim), extreme heatwaves in India (see Earth.com), flash floods in Nepal (see UN, 2024), and storms, floods, and landslides in Pakistan (see Al Jazeera, 2025) and Sri Lanka (see Xinuanet, 2024), have highlighted the critical urgency of strengthening health systems.

Is South Asia ready for the next crisis?

We assessed the health systems’ resilience in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka and at the regional level, drawing on three domains of the ReBUILD for Resilience framework; dedicated leadership and distributed control; availability, capability and motivation of human resources, and availability of physical and financial resources.

Dedicated leadership and distributed control: Do we have the right systems in place?

Robust legal and regulatory frameworks are the backbone of effective emergency preparedness and response, as they define who leads, who decides, and how authority and resources are distributed across levels of government. In their absence, or when mandates are unclear, systems often default to ad hoc, centralised decision-making, undermining agility and coordinated action during crises. All five countries have established governance structures for disaster response and emergency preparedness, though their regulatory frameworks vary in how clearly they define mandates for dedicated leadership and distributed control. India’s Disaster Management Act (2005), Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Act (2010), and Nepal’s Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act (2017) clearly delineate the roles and responsibilities of subnational governments. In contrast, Bangladesh’s Disaster Management Act (2012) and Sri Lanka’s Disaster Management Act (2005) less explicitly mention provisions for subnational decision-making and leadership. While these frameworks establish the foundation for multi-tiered governance, the degree of decentralisation varies across the region. Importantly, legal mandates do not always translate into effective subnational leadership in practice. Roles and responsibilities defined in law are often only partially exercised, largely due to uneven technical capacity, resource constraints, and institutional support at subnational levels, both across and within countries. Democracy Resource Center notes that “local governments lack awareness, resources and technical and institutional capacity to effectively take up disaster management responsibilities” in Nepal (See The Roles of Local Governments in Disaster Management and Earthquake Reconstruction, April 2019).

Several countries continue to struggle with weak inter-governmental coordination, with limited clarity on roles and responsibilities for preparedness and response, and the implementation of integrated approaches, such as One Health, often remains weak. In Nepal and Sri Lanka, for example, coordination across sectors and even between ministries at both national and sub-national levels continues to be a major bottleneck. Furthermore, in some countries, the absence of structured knowledge management systems and handover processes within government institutions leads to significant institutional memory loss, hindering a sustained culture of learning. This forces new personnel to restart the learning cycle and undermines efficiency of the health systems.

While South Asian countries faced immense challenges, there are examples of strategic and flexible leadership to strengthen coordination. The Government of Nepal established a Unified COVID-19 Incident Command System (ICS) – a new coordination mechanism developed specifically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This structure brought together multiple ministries and departments, including health and population, home affairs, and finance, under a single operational roof. By breaking down bureaucratic silos, this structure enabled faster, more coordinated decision-making and streamlined allocation of resources. This prompted ongoing discussions about institutionalising the ICS model for future public health emergencies.

Availability, capability and motivation of human resources: Are we investing enough in health workforce?

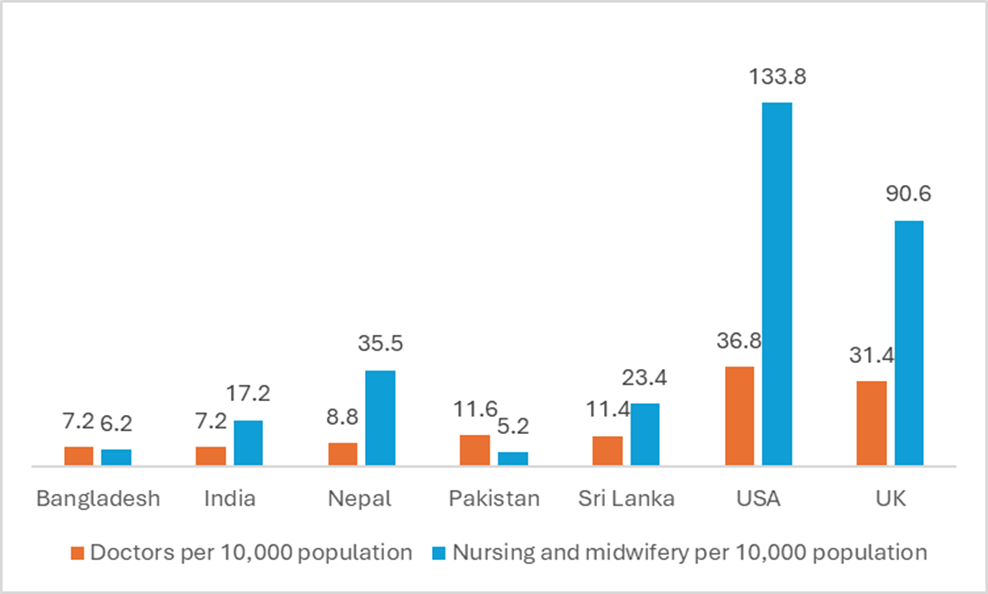

According to WHO Global Health Observatory data, South Asian countries continue to face a critical shortage of health workers compared to global levels and fall short of the SDG threshold of 4.45 doctors, nurses and midwives per 1,000 population (see WHO, 2016).

Fig 1: Comparing healthcare workers’ density: South Asia vs. developed nations (Source: WHO Global Health Observatory, 2025)

All five countries struggle with an acute shortage of skilled health professionals, particularly in rural areas. Limited incentives, low pay, poor working conditions, and lack of career progression discourage health workers from working in hard-to-reach or underserved regions, and the persistent outmigration of the health workforce due to economic challenges continues to weaken the region’s capacity.

This overall shortage of health workers reduces resilience of the health system: there are not enough doctors, nurses, midwives, and paramedics to meet routine needs, let alone to mobilise additional personnel during emergencies. Health workers are often unwilling to move to hard-to-reach areas affected by emergencies due to the lack of incentives and minimal support during crises. Psychosocial support for frontline workers was sometimes minimal, and together with insufficient risk allowances, this results in burnout and demotivation, making it harder to retain or attract staff – for example, as seen with lessons from the COVID-19 first surge in Nepal (see OPM’s Health and Social protection services at local level)

Health system resilience in some countries is also weakened by the lack of clear standard operating procedures or mechanisms for quickly mobilising staff in areas where they are most needed. Our experience across several countries suggests that workforce planning for health emergencies typically focuses on permanent staffing and often overlooks the need for flexible or surge capacity, such as volunteer pools or multidisciplinary training for emergency roles, including for paramedics to take on emergency roles when required. Countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan introduced flexible approaches to expand the health workforce (see Maintains – COVID-19 Series: Synthesis Report, 2020), but these efforts were largely reactive during crises rather than having adequate systems in place beforehand.

All five countries had experienced staffing challenges during public health emergencies, (see UNICEF’s COVID-19 and Migration for Work in South Asia: Private Sector Responsibilities) but there were also examples of rapid mobilisation of additional health workers. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the governments of Nepal (see WHO, 2021) and Pakistan (see Jabeen and Rabbani, 2023) showed remarkable workforce flexibility with staffing for hospitals, using digital platforms to recruit and train new medical staff. Organisations like icddr,b in Bangladesh also tapped into a pool of retired health professionals to strengthen frontline responses. However, while all five countries made efforts to train and rapidly deploy health staff during emergencies, routine training they received often focuses on standardised protocol and often did not consider such pandemic in advance. In Nepal, there was no robust system in place for preparing health workers for emergencies as healthcare training was primarily geared towards routine services with limited emphasis on emergency preparedness (see Current Understanding of Emergency Medicine and Knowledge, Practice, and Attitude toward Disaster Preparedness and Management among Healthcare Workers in Nepal).

Availability of physical and financial resources: Are our health facilities ready for the next crisis?

Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan continue to face overcrowding in public hospitals with limited high-dependency units (HDUs) available outside of urban centres. In Bangladesh,(see Benar News, 2021) India (see Ramakrishnan and Ramakrishnan, 2023) Nepal (see Centre For Investigative Journalism Nepal, 2022) Pakistan (see Khan et al, 2022) and Sri Lanka (see Fernando et al, 2012), the shortage of Intensive Care Units (ICUs) and HDUs is even more noticeable at the subnational level. Many facilities lack proper storage for medical supplies, or such infrastructure is entirely absent, leaving systems and staff vulnerable in the face of future health emergencies.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments rushed to set up makeshift hospitals and temporary isolation centres, and repurposed general wards for infectious disease care. The Government of Sri Lanka showed that rapid infrastructure solutions are possible: when hospitals’ capacity was overwhelmed, emergency care centres were constructed almost overnight with crucial support from the Sri Lankan military. India also demonstrated capacity to scale up ICUs, thanks in part to public-private partnerships. However, while these rapid response measures were necessary (see Future Pandemic Preparedness And Emergency Response), they were often reactive, poorly coordinated and lacked adequate equipment including personal protective equipment (see WHO, 2020). In addition, these efforts were largely short-term and are yet to be translated into sustainable investment, with limited follow-through to integrate temporary facilities, equipment, and workforce arrangements into long-term health infrastructure plans. Across South Asia, many quarantine and isolation facilities constructed during the pandemic, such as repurposed schools in Nepal (see Kathmandu Post, 2025) and large temporary wards in Bangladesh (see Xinuanet, 2020) were either dismantled, abandoned, or left underutilised once immediate pressures subsided. With the shift toward home isolation and the lack of planning to repurpose or maintain these assets, much of the emergency infrastructure has not contributed to lasting improvements in preparedness.

Cooperation between South Asian countries holds significant potential to strengthen the region’s collective resilience in responding to public health emergencies. Although political complexities, siloed responses, and uneven investment in preparedness have sometimes limited the effectiveness of regional collaboration, countries have also demonstrated a growing commitment to shared learning and joint action. The foundation for cooperation already exists and can be further built upon to enhance preparedness, resource sharing, and coordinated responses to future crises. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the power of adaptable mechanisms like SAARC’s emergency fund, BIMSTEC’s technical cooperation on disaster risk reduction, and WHO SEARO’s capacity building initiatives. Global models such as the EU’s centralised logistics and PAHO’s rapid response teams offer actionable blueprints. Going forward, South Asian countries could not only strengthen data sharing through interoperable regional platforms and maintain pre-positioned emergency supplies but also harmonise emergency response protocols, develop pooled procurement and training mechanisms, conduct regular joint simulation exercises, and establish stronger regional governance frameworks to embed trust, coordination, and accountability. These measures would help transform ad hoc crisis responses into a sustained regional health security.

Five key steps to build South Asia’s health emergency resilience

Based on our study, the following priorities could help move from fragmented efforts toward collective resilience.

Reinvigorate political commitment

- Build on existing regional platforms to align priorities and explore commitments to improve health system’s resilience

- Explore a regional pact on emergency health response to formalise protocols for data sharing, workforce mobility, and procurement during crises.

These steps align with earlier regional efforts including SAARC’s COVID-19 Emergency Fund and cross-border disaster agreements in other sectors.

Why it matters: Political leadership is central to unlocking financing, accountability, and faster cross-border collaboration.

Strengthen integrated digital surveillance and response systems

- Build on existing national platforms to develop a regional real-time dashboard integrating outbreak trends, availability of beds and oxygen, and other stockpiles.

WHO’s Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment platform offers a baseline architecture for regional adaptation.

Why it matters: The study found that while most countries have early warning systems, they often operate in silos – within and between countries – limiting timely coordinated responses.

Train, retain, and sustain the health workforce

- Scale up community health workers deployment with specific training to respond to emergencies

- Integrate staff mental health support into emergency preparedness plans.

These align with WHO’s Global Health Emergency Corps initiative.

Why it matters: All study countries faced shortages of skilled staff particularly in rural and hard-to-reach areas and face challenges in rapidly mobilising human resources during crises.

Focus on building resilient and scalable health infrastructure

- Design pop-up hospital blueprints so schools and community centres can transform into care sites overnight

- Retrofit critical health facilities to survive floods, heatwaves, and earthquakes.

Some of the temporary infrastructures (see Himalayan Times, 2020) were built in study countries during COVID-19 pandemic and expanding on them can improve readiness at lower cost.

Why it matters: During recent COVID-19 pandemic, temporary facilities were created which highlights the need for pre-planned adaptable infrastructure able to improve health system’s resilience.

Secure sustainable and flexible financing

- Explore regional pooled funds for preparedness and response to emergencies while building on SAARC COVID-19 emergency fund

This can build upon and seek learnings from European Union Solidarity Fund.

Why this matters: Fragmented donor dependent funding was a major constraint identified by study countries which slowed response time.

The solutions exist: what’s needed is the will to institutionalise them!

The opinions indicated here are those of the author and not necessarily OPM or ReBUILD

Image: Courtesy of Oxford Policy Management